The Freedom Problem

An Independence Day message to my fellow Freedom junkies regarding America's cardinal virtue

This article is the first in a series I intend to write on Anarchism or Anarchy. The draft was finished on July 4th, but the editing process necessitated that it be published the day after. For the sake of poetic satisfaction, please imagine that you are reading this on Independence Day.

If I were trying to choose a perfectly cliche topic to write about on American Independence Day, I couldn’t have done much better than freedom. This word, inextricably tied to the American identity, is so ubiquitous in use that its meaning has been almost entirely impoverished. We all love freedom; indeed the word has so broad a semantic range that there is practically nobody of any political stripe who doesn’t love freedom. The progressive loves freedom, the neocon loves freedom; the populist and the socialist, along with the anarchist and the libertarian, all can shake hands on their love of freedom. Founding Father Fanatics and 1619 devotees are at each other's throats at every turn, primarily because both are such freedom junkies. If one can make the convincing case that a given policy or agenda is indispensable to freedom, then 90% of the rhetorical battle is already won.

And yet each of these factions seems to take a great deal of umbrage at certain exercises of freedom. Freedom is wonderful and all important, except when somebody refuses to wear a mask. Freedom is the essential ingredient to society, and the more freedom the better, unless that freedom is used to talk to children about sexuality. Or if it is used to purchase a gun. Or burn a flag. Or to refuse to pay taxes. We all seem to be engaged in a passionate love affair with freedom, and yet paradoxically the exercise of freedom, when used for a disagreeable purpose, is the cause of our greatest political vexation, and like one caught in an illicit affair we are forced to sheepishly reach for excuses and explain how such and such an issue is an illegitimate use of freedom, how that’s not actually what freedom is for, or to simply capitulate with the browbeaten caveat “I don’t support it, but I support their freedom to do it.” Does anyone actually believe that when they hear it?

It almost seems as if there is a namespace pollution problem. The letters arranged together to form the word “freedom” would appear to be associated with two almost entirely distinct semantic fields. The crudest formulation of this distinction is that freedom has a good and a bad meaning. Freedom can mean either the freedom for me to do what I want, or it can mean the freedom for you to do what I want (but free of coercion, naturally). Now of course this is quite an uncharitable formulation, and I don’t think anyone would explicitly agree to it. But on the other hand the above examples do seem to illustrate that the word freedom can refer to two very different phenomena. To tender some less contentious examples: should you be free to break my ribs and take my wallet? Is it freedom when a group of angry of racists lynches a black man for the simple crime of his skin color? Only the most reprehensible sort of person would tolerate this without an objection. But on the other hand, it would certainly a restriction on the freedom of the racists to prevent them from lynching whom they see fit. One could legitimately make the case that it is repugnant to freedom to prevent a man arrested for child porn from working in a day care. But who in their right minds would even consider this argument? Do we really believe that unbridled freedom is good for society? Surely there must be some restrictions on behavior, and frankly anyone who says anything otherwise, given the above examples, does not deserve a place in civilized conversation.

But of course the very nature of freedom almost requires us to shy away from limitations on freedom. We’re all Freedom junkies, right? We’re red-blooded Americans who don’t put up with any sort of tyranny or despotism. And indeed just as freedom without limitation can lead to some extraordinarily nasty places, the constriction of freedom in the name of perhaps order or the public good can lead to some equally undesirable destinations. Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge programs were ostensibly enacted in the name of curtailing irresponsible behavior in the name of the public good. 2 million Cambodians were killed as a result. Same story with the Maoist Great Leap Forward. How could we expect free, uncoordinated workers laboring in their individual farming enterprises to ever transform China into an industrial utopia? Obviously the solution is to restrain their freedom in the name of the public good, for the betterment of all. Of course that comes with a cost of 45 million Chinese deaths, but surely that’s better than the alternative of simply letting laborers work on their own recognizance, right? Time and again history proffers examples of public-minded restrictions on liberty leading to horrific body counts, from Hitler to Pinochet to Lenin.

Now the classical liberals will make some milquetoast warblings about ordered liberty and how the State can restrict liberty just enough to keep everyone safe, and how the state needs to infringe upon liberty to preserve Rights (whatever those are). But again, does anyone really believe them? (Of course some people do; to these people I would suggest a close reading of Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States before reading further in this essay.) So if we can’t let freedom run amok without descending into a Hobbesian nightmare, and if we can’t restrict freedom without devolving into 1984 tyranny, what are we to do? Freedom seems indeed to be like a hard drug we are all addicted to, and we face the choice between continuing in our life-threatening habit or equally deleterious withdrawal symptoms.

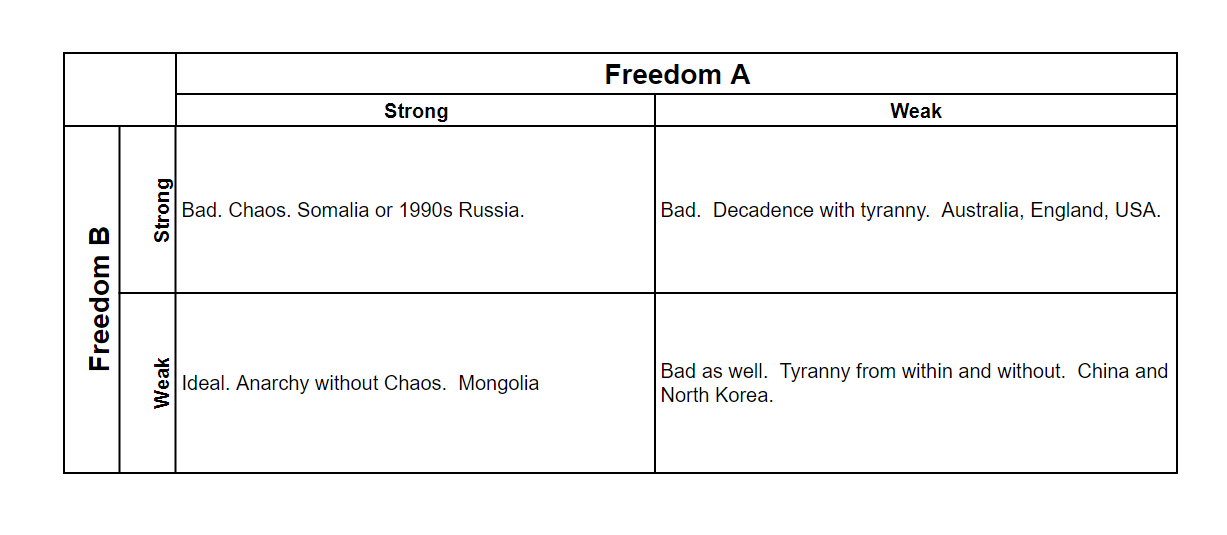

This is why I propose namespace pollution, or perhaps we could call it toxic homography, as a frame for this problem. If damnation comes from both a lack of freedom and an excess of it, might it be that these are simply two different phenomena? Could it be that the word freedom needs to be disentangled into two separate words, spoken of as two entirely different phenomena, with only tangential correlation? Well unsurprisingly this is precisely what I propose. For simplicity’s sake I will refer to these as Freedom A (for Anarchism) and Freedom B (for Barbarism). I think the best way to formulate the distinction between these is this: Freedom A is the lack of tyranny, or coercion, or oppression, whereas Freedom B is the lack of any restraints at all. Freedom A can be associated with words such as liberty, self-government, independence, etc., whereas Freedom B has more to do with antinomianism, libertinism, chaos, etc. Freedom A can be summed up in Noam Chomsky’s formulation “The burden of proof has to be placed on authority, and that it should be dismantled if that burden cannot be met”; Freedom B adopts the Redditor’s refrain “Just let people do what they want!” as its motto.

In this framing, Freedom A and B are almost antonyms of each other, since it is hard to imagine a world with a complete lack of restrictions on people’s behavior in which tyranny does not quickly develop. Saliently, Freedom A is a fundamentally negative concept, only defined by the absence of something else, whereas Freedom B is a positive facility which can be either present or absent. Just as one cannot define darkness apart from light, Freedom A doesn’t really have any meaning apart from an absence of something else. By contrast, Freedom B is something in and of itself, and we can tell whether or not it’s “there” independently of any other ideals. Finally, when Freedom A is what I refer to when I speak of anarchy or anarchism; the project of anarchism is to maximize Freedom A without devolving into the Hobbesian nightmare.

This distinction begins to elucidate why we can refer to freedom as both a positive and a negative thing. For those so inclined, Freedom A represents the Lockean vision, that cherished ideal of “Ordered Liberty” so uncritically revered by Founding Father Fanatics (and actually the Fathers themselves). On the other hand, Freedom B represents the Hobbesian nightmare, a “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” life beset by violence and assault. Two very different ideas indeed. So when we ask the question, “Will the proliferation of freedom lead to a Hobbesian nightmare?”, the correct answer is “Depends on what you mean by freedom.” If we blithely and indiscriminately go about removing any and all restrictions on a person’s ability to do what they want, haphazardly maximizing Freedom B with no regard to consequences, then the result will almost certainly be the Hobbesian nightmare. The Non-Aggression Principle, that notorious Libertarian mantra, “No man or group of men may aggress against the person or property of anyone else,” sounds like an effective rule for a society, but ends up being castrated and rendered impotent against the brutal realities of mankind’s nastier proclivities. It’s all well and good to talk about not initiating force against anyone else, but this platitude by itself will not restrain the tides of human jealousy, resentment, rage, not to mention susceptibility to propaganda and manipulation. No, it will take some other force more efficacious than Rothbardian banalities to restrain the might and awfulness of humanity.

Freedom B also has another problem, related to its nature as a positive rather than a negative notion, which must be reckoned with. A negative concept can be pursued simply by identifying that which is undesirable and rooting it out where it appears. Of course this can devolve into a witch hunt, but in general the limitations of a negative enterprise are clear: the job is done when X is no more. (This is why anarchism is a fundamentally negative term - an meaning “not” or “without”; this is something I will treat in the 2nd essay in this series). But a positive concept - the ability of anyone to do what they want, absolutely free of restrictions - has no conceivable limitation or terminus on its proliferation. Freedom as a positive ideal turns into a cudgel used to impose one’s values on the majority. For the Freedom B enthusiast, any situation in which they don’t get their way is a lack of freedom which needs to be rectified. Because Freedom B is an absolute concept, the lack of any restrictions on people’s behavior, any sort of obstacle to the realization of their desires is anathema and must be eliminated. Political discourse turns into “I didn’t get my way, and that’s your problem.” It only takes the most marginal ironic sensibility to see the humor in this use of freedom.

But there is nothing in Freedom A that necessitates descent into such a chaotic, violent scenario. Even if taken to its maximum, I see no reason why the absence of tyranny, of overreaching and overbearing authority, must necessarily lead to the dissolution of all order in a culture, or must turn into a baseball bat with which to beat on freedom-hating brats. As Peter Kropotkin points out,

We know well that the word ‘anarchy’ is also used in current phraseology as synonymous with disorder. But that meaning of ‘anarchy’, being a derived one, implies at least two suppositions. It implies, first, that whenever there is no government there is disorder; and it implies, moreover, that order, due to a strong government and a strong police, is always beneficial. Both implications, however, are anything but proved. There is plenty of order — we should say, of harmony — in many branches of human activity where the government, happily, does not interfere. As to the beneficial effects of order, the kind of order that reigned at Naples under the Bourbons surely was not preferable to some disorder started by Garibaldi; while the Protestants of this country will probably say that the good deal of disorder made by Luther was preferable, at any rate, to the order which reigned under the Pope.”

If we have proper and well-defined criteria (which does turn out to be a difficult task, but certainly an achievable one; see the second essay in this series for more), tyrants are very easy to identify. If all that we seek is to extricate improper authority, there is no reason, either historical, logical, philosophical, etc., to suppose that the tyranny of the masses will necessarily ensue. Now I am not claiming that Freedom A prevents any and all negative outcomes; all it does is prevent one specific negative circumstance - tyrannical centralized power. If Freedom A is only able to accomplish the exclusion of dictatorships and mass exploitation/extortion, then I would say Freedom A has done very well for itself indeed. (It ought to be pointed out here that the government is not the only source of tyranny; any entity wielding undue power over a population, such as a local warlord, an exploitative corporation, The Cops, etc., could all be considered tyrannical. But by the same token, all of these entities may be dissolved and Freedom A taken to a maximum without necessarily leading to a complete devolution of society.)

Now of course the danger in all of this lies in the operative qualification “necessarily.” The proliferation of Freedom A doesn’t necessarily lead to the Hobbesian nightmare. But it doesn’t prevent it either. In fact it often does lead to such a dissolution of social order. Whether or not one likes tyranny, one can’t help but admit that it is indeed a stabilizing force for society, as is any authority. The historical record teaches us that when the State or some other source of strong central authority is removed, very often a very dark period ensues. One only needs to look at post-Soviet Russia, Revolutionary France, or Rome after the collapse of the Empire to be convinced of this point. The problem with Freedom B is that it leads to the Hobbesian nightmare. The problem with Freedom A is that it is delicate, very easily confused with and parasitized by Freedom B; it has no mechanism for preventing dissolution into barbarism. In fact, Freedom A will not work if a society has no other restraints on its behavior other than external, centralized authority. If the removal of strong tyrannical restraints is to succeed, it is essential that some sort of voluntary, internal restraints govern people’s behavior. The chart below illustrates my point.

The lesson in all of this is that, if the project of anarchism is to succeed, if we as American freedom junkies are to get our fix without descending into the ravages of an addiction, society must be sufficiently bulwarked against barbarous freedom. A barbarously free society needs some force to curtail its decadence and violence, or else all the fears of the conservatives will come true (an unpleasant prospect on several different levels). Now of course the existence of some external/artificial curtailing force, such as the State doesn’t actually guarantee the restraint of Freedom B. Not only is it possible for the State to exercise its tyranny in ways which do nothing to restrain the more vile impulses of humanity (see: the Holocaust, an example of tyranny which actually accelerates these vile impulses), but a decadent, unrestrained population sinking under the weight of its own wanton lack of restraint is actually much easier to control than a population with strong internal restraints on its behavior. A society given over to the ravages of Freedom B(arbarous) is more or less doomed, whether or not there is a State exercising influence over its behavior.

I suppose my point in all of this is that, although I don’t think that us Freedom addicts need to give up our drug of choice, maybe we should exercise a bit of restraint in our habit. Even given the difficulties and delicateness of Freedom A, it still seems to be preferable to any alternative. Barbarous freedom damns any society it infects, but at the very least Freedom A prevents one specific type of tragedy - that of the oppressor, the manipulator, the tyrant. Or in the words of Gustave de Molinari: “Anarchy is no guarantee that some people won’t kill, injure, kidnap, defraud, or steal from others. Government is a guarantee that some will.” Given the choice between a society surrendered to its basest impulses that has a tyrant in place or one without such a tyrant, I would choose the latter every time. It wouldn’t even be a hard choice. But if we are really serious about exorcising tyrants, fortification against barbarous freedom must come from somewhere. Culture, religion, and voluntary agreements all provide options. As Daniel Schmachtenberger points out, there are about 5 million Buddhists in the world, with no central authority constraining their behavior - and in general they don’t hurt bugs. The defenestration of tyrants is certainly desirable, but we simply must be careful that our defenestration doesn’t lead to further tyranny.

But to reiterate: We don’t need to give up our drug of choice entirely, but we must be careful to keep the good dope separate from the bad. If we waltz around the public square trumpeting about FREEEEEEEDOM, we are bound to get people hooked on the bad kind of freedom and will unintentionally be advocating for some pretty dreadful things that we don’t at all support. It might not change much on the ground level, but some nuance and distinction in our treatment of the word “Freedom” might do a good deal to improve our conversations around the topic. In any case, I hope this can provide a bit of an answer for those who seek to defend their Freedom habit against interventions from well-intentioned Statists and the like. Not that we need to surrender to compromise; far from it. Freedom (A) ought not to be sacrificed for the mundane practicalities the “adults” often weaponize to belittle the ideals of anarchy. But maybe we should exercise a bit more restraint and caution in our orgiastic discussions of Freedom. A modicum of self-control might do a lot of anarchist Freedom junkies a lot of good. But hey, what am I doing, telling you how to talk about Freedom? Let people do what they want, right?

Congratulations! You made it to the end of another Anti-Propaganda Gazette Article! Since you’re obviously a connoisseur of anti-propaganda and a tasteful sophisticate to boot, why not subscribe to my column for even more quality literature?